Sunscreem Biography

by Paul Lester, September 2009. Taken from 'Love U More' (2009) sleeve notes.

Sunscreem are one of the most important bands in the history of British dance music. And they were a band, which is crucial to their success and their story.

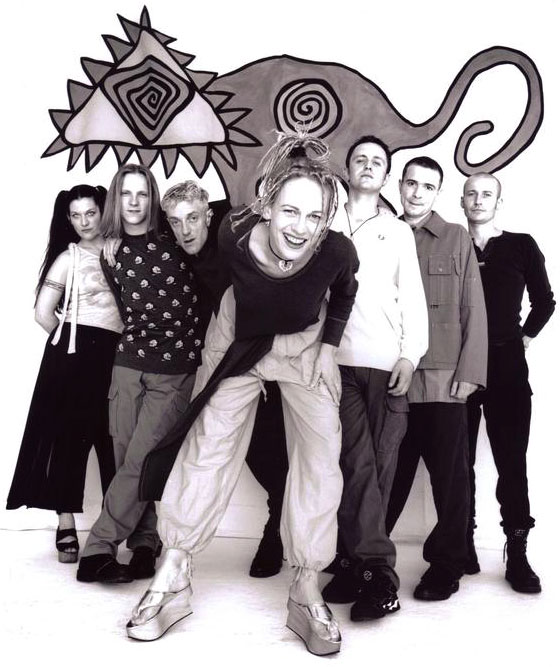

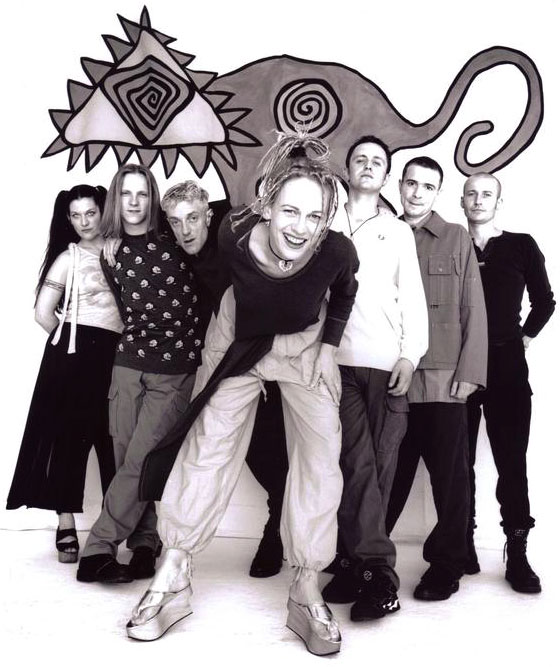

More than just a faceless DJ or a photogenic vocalist fronting an anonymous backing troupe, they were a proper, fully-functioning recording and performing unit who made several superb albums and gained a huge following among both the hiperati of clubland and fans of mainstream pop, not just here but in the US.

They had UK and US Dance chart Number 1s, which is more than can be said of any group of their type – if indeed there has ever been a group like Sunscreem. And their influence has been far and wide.

Without their groundbreaking recordings, and pioneering work in the area of live performances – breaking the mould of the standard club PA by performing with a full live band and the sort of elaborate visuals you’d only see at raves, free parties and clubs – it could reasonably be argued that outfits as far removed chronologically as Republica in the ’90s, Faithless in the early ’00s and Pendulum today wouldn’t have been able to proceed as they did. Meanwhile, even the superstar Madonna has acknowledged that without the inspiration of Sunscreem, she might not have been tempted to dip her toe in the acid house waters, as she did on her Ray of Light album.

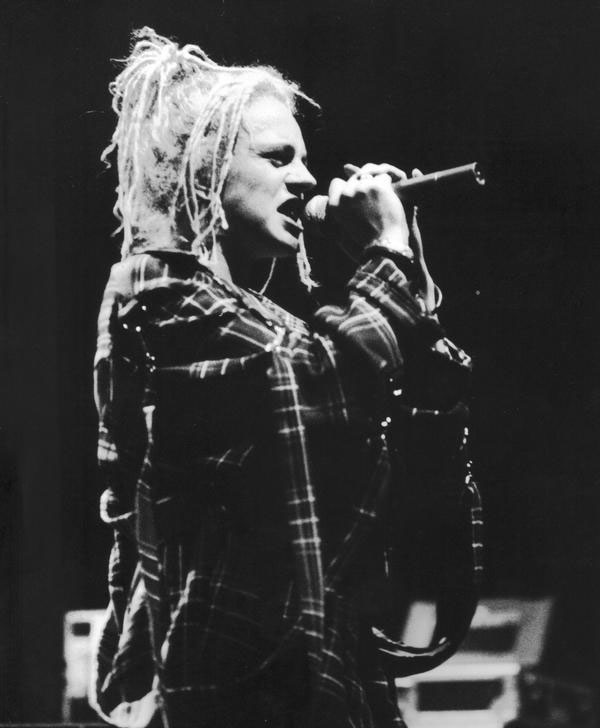

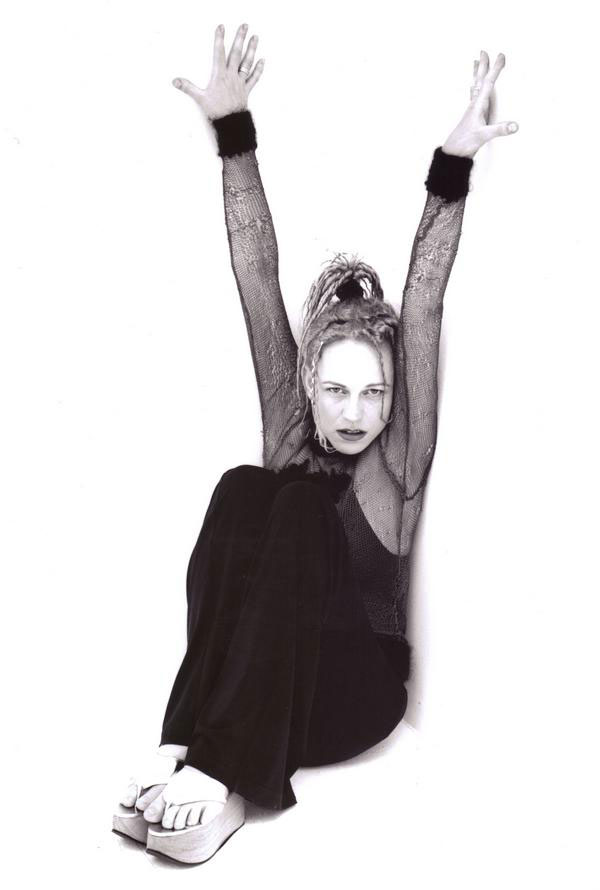

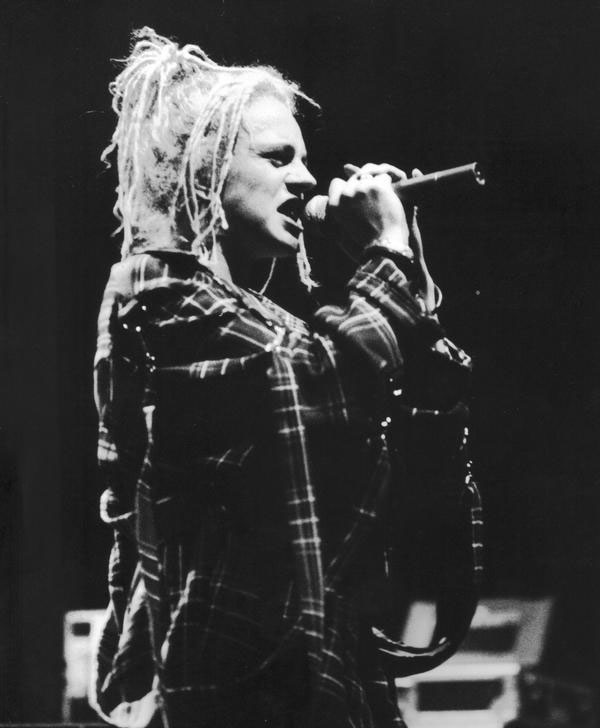

Their music was eulogised in the press as “ethereal, blissed-out dance pop,” their live shows praised as “adrenaline-soaked, all-singing, all-dancing, all-flame-throwing events,” their singer extolled as a “dreadlocked harpy from Heaven,” while Sunscreem themselves were hailed as “the best dance band on the planet.” But their story reaches back further than you might think, to the early ’80s, when Paul Carnell, a self-styled “electronic geek,” met Lucia Holm, a half-Finnish, classically trained cellist/bassist turned singer-songwriter. The two played in Shot The Rapids, a Chelmsford-based synth outfit who used live sequencers and real drums, with Paul’s brother on vocal duties. In 1985, Duane Brazier, a gifted drummer, replaced the band’s original stickman.

Within a year, they were in the studio with Andy Taylor of Duran Duran, collaborating on an album, although it was never completed. “I remember Andy walking in the first day and saying, ‘I won’t try to tell you about music’,” recalls Paul, “‘but I can do this’ – and he plonked two bottles of vodka onto the studio table-top and said, ‘Let’ have some fun!’’ So we got quite drunk. He taught us a lot about catching a vibe in the studio.”

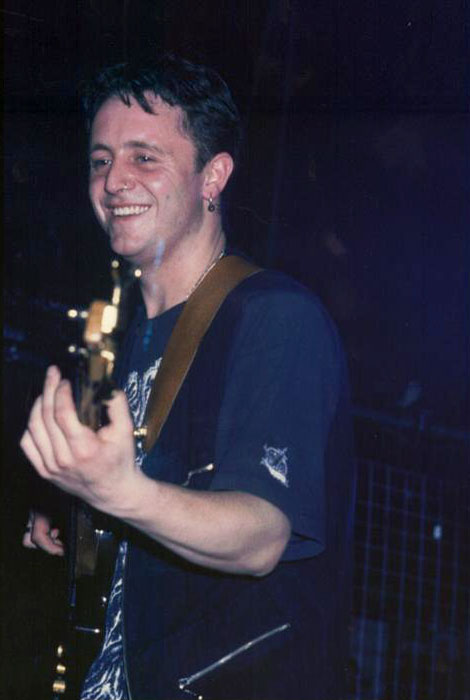

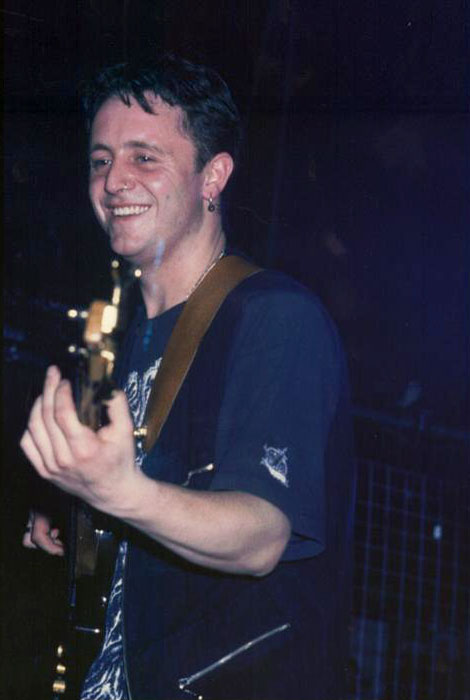

Back in Essex, the promoters Mangled started a seminal club at the Braintree Barn, Essex’s equivalent to Manchester’s Hacienda, with Mr C, later of The Shamen, DJing. Here Paul, Lucia and Duane met Gary “Baz” Bailey (later Sunscreem’s “groover” – their onstage dancing mascot à la Bez of Happy Mondays), as well as Keith Flint and Leroy Thornhill, who would both achieve a modicum of success with a group called The Prodigy. The club always had a PA act, often rather poor, and this inspired Paul, Lucia and Duane to re-group as Sunscreem with the intention of being a fully-performing dance-pop unit with live sequencers and drums. Lucia was persuaded to sing, with Rob Fricker on bass and old friend Darren Woodford, a local whizz kid recording engineer, on guitar and mixing duties.

Finally, they recruited DJ Dave Valentine and Aldo Soldani, who with his brothers provided lights, banners and general live direction for the band as they sought to replicate the rave experience on stage.

Sunscreem became so effective live, and so fast, that they signed to Sony Records after just six gigs. After a period of relentless gigging, during which they played hundreds of shows, Sunscreem finally recorded some tunes. They convinced the record label that remixes of their music were essential to break the records in the underground clubs and launch them into the mainstream charts, insisting on the use of up and coming DJs and artists such as Leftfield, Carl Cox, Slam and Farley/Heller.

They made the best start possible: Love U More, issued in July 1992, was an irresistible techno-pop surge that simultaneously reached Number 1 in all three UK dance charts – RM, Mixmag and Music Week.

By the following March Sunscreem were at pole position in the UK and US dance charts with different tracks – Love U More in the States and Pressure US in the UK – both of which went on to become worldwide dance anthems. For the next five years Sunscreem were a ubiquitous presence in clubland and in the charts, enjoying 7 Top 40 hits including Love U More, Perfect Motion, a version of Marianne Faithfull’s Broken English and Pressure.

Sunscreem weren’t just adept at the three-minute singles and choosing remixers. Their first album O3 sold over 300,000 copies in America, where it was the biggest-selling UK debut album in 1993.

They toured America and Canada with Inspiral Carpets on the back of the success there of Love U More and followed this with a tour of arenas and amphitheatres with New Order.

After a prestigious collaboration with pioneering electronica artist Jean Michel Jarre [sic] and the use of Pressure as title track for the Geena Davis movie Angie, they recorded their second album Change Or Die.

This contained the two enormous club anthems, When and Looking At You, (for which they won an ASCAP award) which sealed their reputation on the burgeoning American party scene and kept them busy playing live in the States for the best part of a year where they enjoyed three Billboard dance Number 1s and two Billboard dance Number 2s.

There were, however, some low points, particularly the departure of founder members Darren and Duane and the tragic death of Aldo in a car accident in 1994, an event which devastated the band. The second album was delayed by nine months or so, and its tone and content became preoccupied by what had happened.

“He glued the thing together and was an accepted authority on what was cool,” says Paul. “After joining the group he famously went through all of our wardrobes throwing out clothes he didn’t like. After he died the band unraveled.”

At this point record company politics also intervened and when Sony refused to release their second album in America, the band negotiated their release from the label. They signed to the infamous Pulse-8, home of Pizzaman and Urban Cookie Collective, but unfortunately the company went belly-up after six months, leaving the band with a new unreleased album to add to their problems.

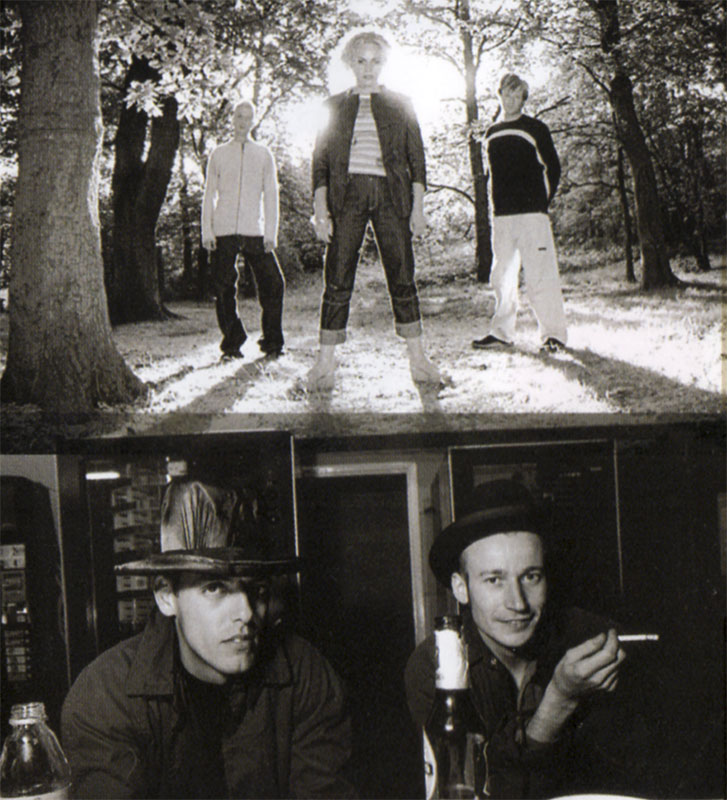

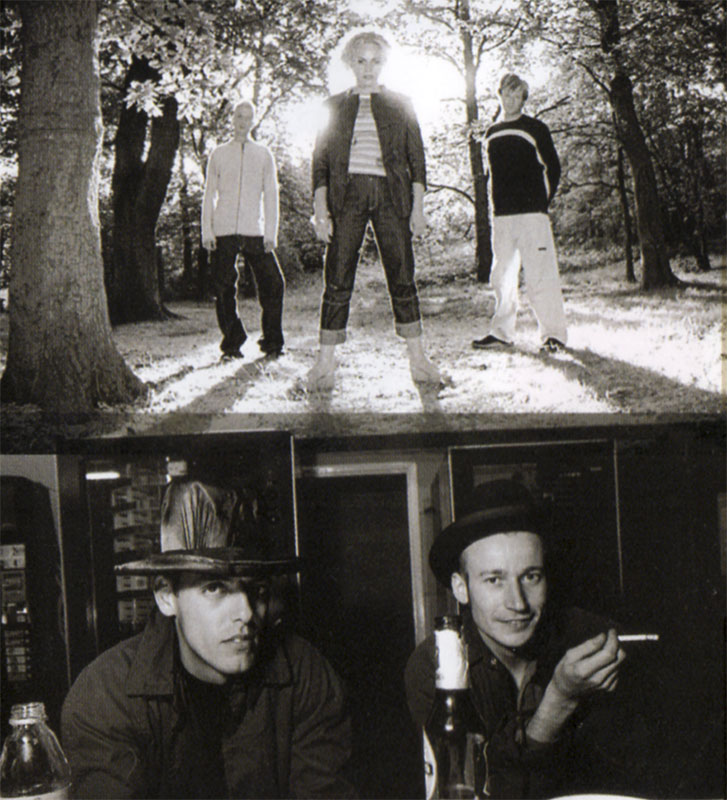

Nevertheless, in 1997, Lucia and Paul, teamed up with Nick Slingsby (aka “Bongo Ted”) on percussion and enjoyed a second period of success in the States in the wake of the massive club success of When and Looking At You. “In a way we broke America twice,” says Paul.

Paul, Lucia and Ted still do gigs as Sunscreem. Carnell laughs when he remembers the busy, bustling line-up onstage in the early days, and the attempts by Sony to market them more as a sort of rave-era Blondie, with the “attractive girl with a good voice at the front, and the bunch of lads wearing black at the back,” a scheme that was foiled by Sunscreem’s numerous musicians, DJs and dancers.

Joking aside, Paul believes Sunscreem made a serious contribution and merit a place in the dance-pop pantheon. He’s right. Perfect Motion combined infectious pop hooks with the rhythmic momentum of the best techno and house and sealed their place in dance music history.

With no support from national Radio 1, the sheer strength of club and specialty radio play catapulted the single into the UK Top 20. Their singles consistently charted around the world while the group played over 500 shows to hundreds of thousands of people. But it was their experimentation with different genres – the mixing up of rock dance and pop – that was so groundbreaking.

“We paved the way for a lot of acts,” says Paul. “An indie pop band immersed in club culture – that was us. We proved you could do live PAs and gave confidence to other bands to reach out and embrace aspects of the rave scene. We also used remixing as part of the overall creative writing process, taking ideas from the DJs and incorporating them in our live sets. On occasions a remix would spawn a completely new track. I think this may be part of why the music connected with such a disparate demographic. As far as I know, no other bands did this.”

Gallery