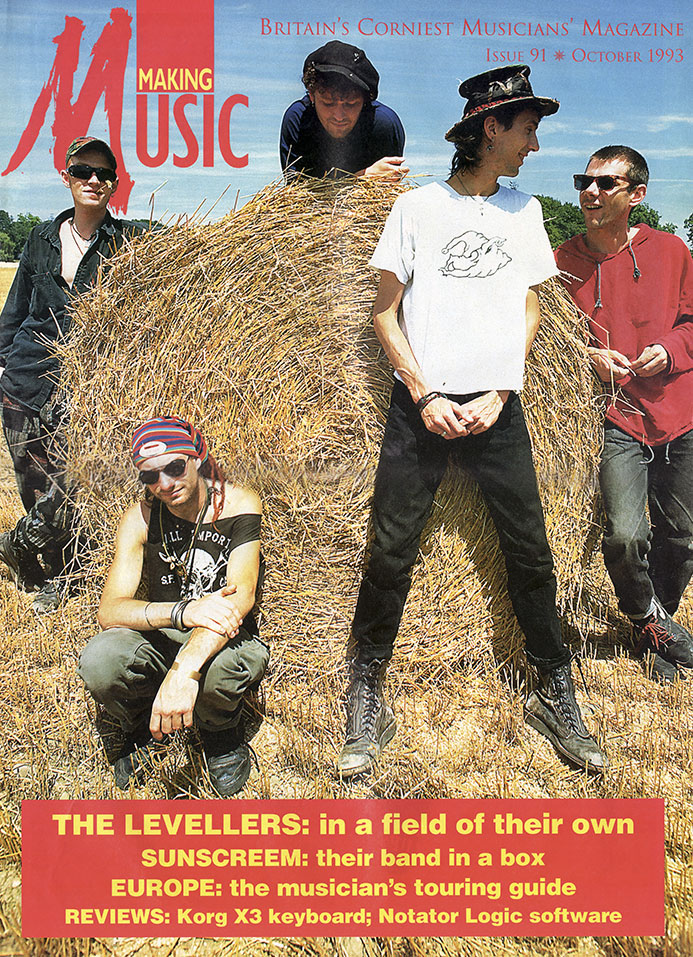

Sunscreem: Their Band in a Box

by Andy Parker / Making Music Oct 1993 / © 1993 Making Music

Today’s modern marriage of technology and performance has proved a mixed blessing for some bands. With the advent of cheaper and smaller studio equipment, it should be possible for acts that previously only existed in the studio, to become ‘live’; and for ‘rock’ acts to play dance music, previously the province of recorded music only. But problems still persist.

Bands that mix live guitars and amps with drum machines on stage still suffer particular difficulties in setting their stage levels, as well as the distinctly unappealing visual aspect of the two blokes with guitars trying to get the audience excited by dancing around a little drum box.

In dance clubs, the sound systems are not generally set up to interfere with either concert-type PA rigs, or the dynamics and transients of a live act playing through their speakers.

All they want is for the act to get up, play and then go. And so has come about the ‘Personal Appearance’. No feedback, no amps, no 35 microphone soundcheck, no playing heavy metal tapes to EQ the rig, the best of all, no drummers. No one likes drummers.

The approach taken by Sunscreem, who reached the Top 30 with their version of Broken English, has allowed them to play both rock gigs and raves using the same equipment. With no amps on stage, the band have condensed their entire backline into two 19in racks. Their rig, comprising half their studio gear, delivers a stereo submix of a drum kit, guitar, bass, keyboards, vocal and DJ line-up to the Front of House [FoH] desk down just two wires. Left and Right. The system also delivers the on-stage monitor mix through the band’s integral foldback system.

By reducing their requirements from a PA system to the use of two XLRs or a couple of phono-ins even, they can play anywhere in the country that has a stereo amp. They could even play your front room. Frightening.

On the Rack

Unusually, the band use neither a standard MIDI-computer nor a dedicated sequencer to provide their patch changes and clicks.

“We’ve got a Toshiba, a T3200,” explains bassist Rob Fricker. “It’s about five years old, it’s been virtually round the world, it’s been in every sweaty nightclub and rave in the country and has never packed up on us. Never crashed, never locked up. It’s a laptop and sits on top of the racks. The reason we use it is because it has four MIDI ports, so you’ve got 64 MIDI channels, four groups of sixteen. We use Voyetra Sequencer Plus Gold, a really tacky name. It’s American software, IBM-compatible. We’ve got a Notator we use sometimes in the studio, but the Voyetra is such a workhorse, it’s so reliable. We talk about ‘Tosh’ as, like, the sixth member of the band. We was even thinking of buying him a little outfit.”

The keyboard rack contains a Roland S-770 sampler, an Akai S1100 32MB sampler and a brace of Oberheims, amongst others. The keyboard sounds are controlled from a Roland A-80 mother keyboard.

“The 770 is used mostly for fragile old bits of kit that we can’t take out because they do two gigs and fall apart. We’ve got a collection of old synths and stuff dating back to the Vox Continental. The 770 gives a slightly wider frequency response than the Akai. For old analogue sounds we tend to use the 770 because it’s that little bit more… authentic. I use Roland Alpha Juno 2 [for keyboard bass on stage], but the sounds are out of the sampler. All the samples are on hard disk so we load them up on the computer; just say ‘load the samples’ and it’ll load them all.”

The keyboard rack also contains the drum mixer and a Roland drum machine to generate the click track for their drummer Sean Wright. On stage Sean uses the ddrum II electronic pad kit to generate his sounds.

“Sean used to have a real snare triggering a sound from a crap drum machine to save having to mike the kit up. The ddrum is a fantastic set-up, and we’ve also got him linked up to the Akai S1100, with sounds sampled off his acoustic kit. We cut up break-beats, then trigger the sounds from the sampler and the ddrum at the same time. When you see him playing it you think, ‘nah, it must be a loop’. They’re all cut into little bits and triggered.”

When playing live, Sean prefers to hear the click through the monitors rather than wear headphones; he uses a conga pattern around the beat rather than a simple four-to-the-bar cowbell click. One problem with an on-beat click is that it can only properly be heard in the foldback if the drummer is out-of-time (since the click is largely obscured by the on-beat rhythms of the song), or unless it’s cranked up to maximum volume in the foldback, which then bleeds onto any cymbal mikes, and doesn’t do much for your ears either.

The second rack is used for the guitar amps and signal processors and connected to the first by a 96-pin multi-core connector. Like Rob, Darren Woodford, Sunscreem’s guitarist, has no backline on stage and pre-amps his guitar through this rack, monitoring it via his wedge monitor.

“Darren uses the ADA MP1, which is a tube pre-amp, a MIDI-programmable one.” Out of the ADA, Darren goes into a Palmer Speaker Simulator in a 1U rack, which also acts as DI box, and through a dedicated SPX90. “The Palmer really does grunge your sound up; it’s not far off sounding like a miked-up Mesa/Boogie. It buzzes and farts and feeds back. Darren’s an SG man [though he’s also got a Gibson Firebird]; he gave up on using Les Pauls because of the neck-ache.

“My bass guitar goes into an Ampeg SVT pre-amp, comes out and into a Drawmer compressor to limit it, not the volume, but the bottom end. I use a Gibson Les Paul bass, strung B E A D, because I’m a five-string bass player really. I started using Les Paul because it’s passive, so I don’t have to worry about batteries. With active basses and radio packs and loads of keyboard stuff on stage, you get a lot of interference.”

Lucia Holm, the lead singer, also has an Alpha Juno 2 keyboard to play additional parts at the gigs. Her vocals go through a radio microphone to the sub-mixer. By sending patch changes from the sequencer, the settings on her Lexicon PCM 70 can be continuously altered during the set, allowing the reverb or echo to change for a phrase or even a single word.

In the Box

What They Say

“A lot of dance acts are just a producer who does all the programming, then hires someone to sing. We’re probably the oddest dance music band, because there are so many of us. Everybody is playing the major parts. The sequencer is there as an enhancer. Unless you want to physically change the sounds on 30 or 40 different settings before each track and still get a 45-minute set in, it has to be done that way.”

Despite the band playing their instruments on-stage, some people still believe they are miming. On one occasion someone reached out from the audience while Rob had his hands in the air and slapped the strings on his bass to see if it was plugged in.

“There was this boy and girl standing there and he’s going to her ‘Go on, he won’t have a go at you. Do it.’ And her hand goes BONG! – 30,000 watts across the stadium. She was like, ‘Oooh, I’m ever so sorry.’ ‘It’s OK,’ I said, ‘don’t worry about it;’ 30,000 people knew my bass was plugged in.”

What would the Sunscreem audience hear if all of a sudden, the whole band dropped dead on stage? “Well, it would definitely not be a Milli Vanilli,” says Rob, nearly anticipating my next question. The last time I saw Sunscreem play they were using sampled backing vocals and Rob doubled keyboard bass parts. This they no longer do, and all the vocal parts are now performed live. “You’d only hear a click and a couple of boring chord pads.”

“We’re still compromising. Even after having spent bloody loads of money. But we haven’t just spent the money for it to work live, it’s our studio rig. I wouldn’t get up and play to a DAT. It’s alright for people who haven’t got the same facilities as us, but for us this is ideal. We’re a very Nineties band, probably the most innovative band of the Nineties.”

Gallery