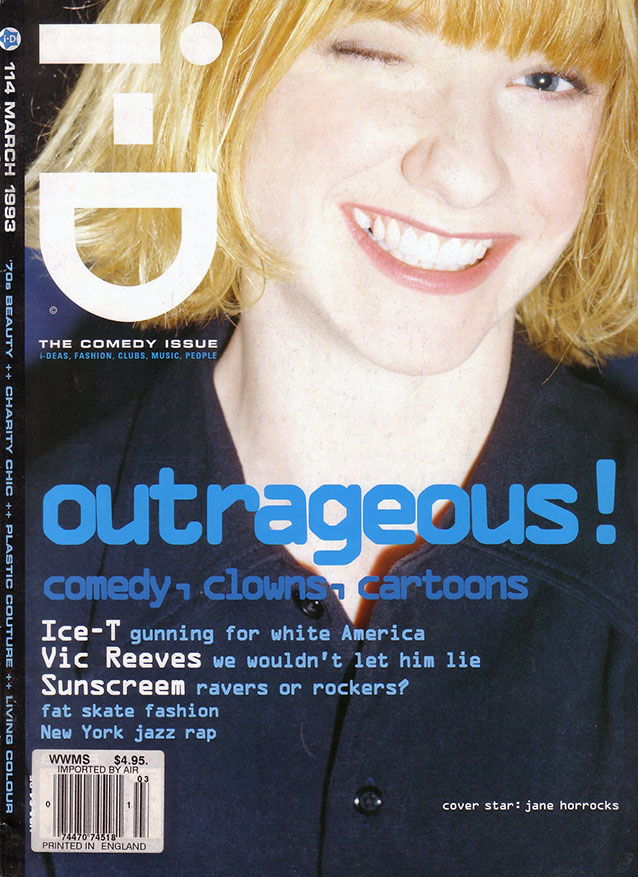

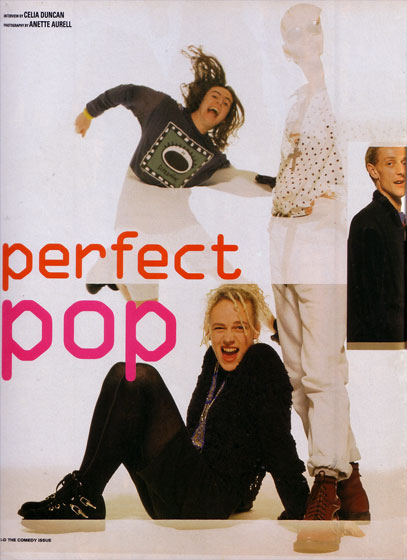

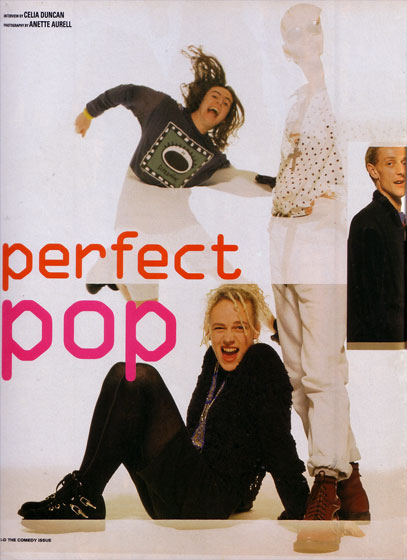

Perfect Pop

by Celia Duncan / i-D The Comedy Issue No. 114, March 1993 / © 1993 i-D

A chart-friendly combination of dancefloor rhythms and singalong tunes, Sunscreem are a marketing man’s dream. But they’re determined to follow their own path…

The only problem is, they don’t want to. The only way, it seems, to satisfy the conflicting quinquereme is to keep “five feet in five different music camps,” as Paul Carnell puts it. “We thrive on paradoxes.”

The underlying enigma of Sunscreem is how Top Of The Pops regulars and major label signings can sell so well in independent record shops. The answer, perhaps, lies in the quantity and diversity of their remixes. Last year’s melancholy Perfect Motion was retailored as frantic hardcore by Carl Cox, trance-techno by Leftfield and hypnotic sequential synth chords by Boys Own’s Terry Farley and Pete Heller, thus satisfying every subdivision of house music in clubland.

The rerelease of Pressure this month will be the third track to be transformed from mainstream High Street to a club couture sound by the Boys Own duo of Farley and Heller. The incongruity of Essex ravers working with the cultural élite of the club world is admittedly puzzling. “The songs stand up on their own. We’re not working with people just because they’re trendy,” explains Terry Farley. “I’m very against remixing Paul McCartney and Lulu records – they’re just using house music to sell a product. Sunscreem are genuinely into it.”

Sunscreem’s roots are unashamedly Summer Of ’88. Even though only three out of the five – Lucia, Paul and Darren – were playing together at this stage under the name Shot The Rapids, the early rave influence reoccurs throughout their album whenever the familiar acid SH101 modulator warps the pitch or Balearic piano riffs dominate an instrumental. “The second time I was out raving I heard a track with a rock riff and a house beat,” says Lucia. “I don’t know who did it but I immediately went back and tried it out for myself.” The result was Psycho, the last track on the album. “That’s how we get a lot of our inspiration.”

Sean Wright and Rob Fricker were adopted into the rural collective in February 1990. From organizing their first appearance at a rave in East London to spontaneous parties at a 14th Century milking shed in Chelmsford (which is now their 24-track studio, The Retreat), Sunscreem began to carve themselves an individual niche in the club circuit.

From organizing their first appearance at a rave in East London to spontaneous parties at a 14th Century milking shed in Chelmsford (which is now their 24-track studio, The Retreat), Sunscreem began to carve themselves an individual niche in the club circuit. They are one of the few rave acts to incorporate live instruments into an otherwise synthesized set as opposed to miming to a DAT tape, and create catchy, chart-friendly refrains that transcend the confines of the dancefloor.

Their record label, Sony Soho Square, are open about their intentions to mould the group into an internationally successful pop group. With the continued overall decline in the singles market, major labels need to sell albums to recoup their investment in new bands. This has, inevitably, proved a problem with dance acts who are more at home on white label remixes than CDs. “Singles don’t make money,” states Diane Young, A&R Manager at Sony Soho Square, who signed Sunscreem. “They are just promotional tools to raise awareness.” With O3 released simultaneously in the States and Britain, Sony are aiming Sunscreem for the global mainstream. “What they are doing – combining strong songs with dancefloor ideas – is very interesting,” continues Young. “I think they’ll be one of the first acts to break through form the dancefloor and sell albums.”

Sunscreem, however, don’t feel entirely comfortable with this. “At the end of the day they want to turn us into pop icons, as all the dance stuff is on the whole pretty anonymous,” says Paul Carnell. “They’re just trying to sell a product – it’s as cynical and calculating as that.”

The marketing strategy inevitably means using an easily identifiable figure-head to front the act. Enter reluctant Lucia. “Lucia had this really distinctive look – the blonde Rasta hair and everything,” says Sony’s Diane Young, recalling her first impression of the band. “I thought it was really unusual. You get a lot of dodgy boilers fronting acts, but here was a woman who didn’t need to wear a mini-skirt to attract attention.” Lucia undermines the blonde-bombshell-fronts-faceless-male-backing-band cliché by spending much of her onstage time on the backline, playing keyboards, only heading stage front to deliver the vocals.

A certain confusion about who Sunscreem actually are (lack of frontperson, anonymous packaging, club pedigree) has held them back to some extent. “Radio 1 has never palylisted any of our tracks,” protests Lucia, “and Gallup (the chart compilers) knocked Love U More down from its original chart position because they thought something funny was going on in the independent record market.”

“The music business gets frustrated because they don’t know where to place us,” laughs Paul. “They didn’t create us or manufacture us like they did with Suede, for example. We did it ourselves.”

There’s another paradox, between Sunscreem’s easy-listening music and the brutality of their lyrics. The swirling, melodic vocal line of Pressure masks the claustrophobia, isolation and pain expressed in the words. Similarly, in Love U More, the lyrics “We can turn wine into water / As fathers rape their daughters,” an attempt to convey the underlying brutality of contemporary society despite technological advances, were masked by melody and went uncensored by the BBC on Top Of The Pops. It’s this hybrid, both musical and lyrical, that keeps Sunscreem one step ahead. “We take the clichés of the music world and pervert them.” Paul’s eyes light up mischievously. “Yeah – what we’re really trying to do is destroy the whole music business.”

Gallery